Oboe 1

Gordon Hunt

Oboe 2 / Cor Anglais

Alison Alty

Flute 1

Thomas Hancox

*Alex Jakeman

Flute 2 / Picollo

Christine Hankin

*Alyson Frazier

Clarinet 1

Mark van de Wiel

Clarinet 2

Jonathan Parkin

Bassoon 1

Meyrick Alexander

Bassoon 2

Graham Hobbs

Horn 1

Ben Goldscheider

Horn 2

Annemarie Federle

*Elise Campbell

Tam-Tam

Elsa Bradley

Conductor

Hannah von Wiehler

*indicates performer in Seascape only

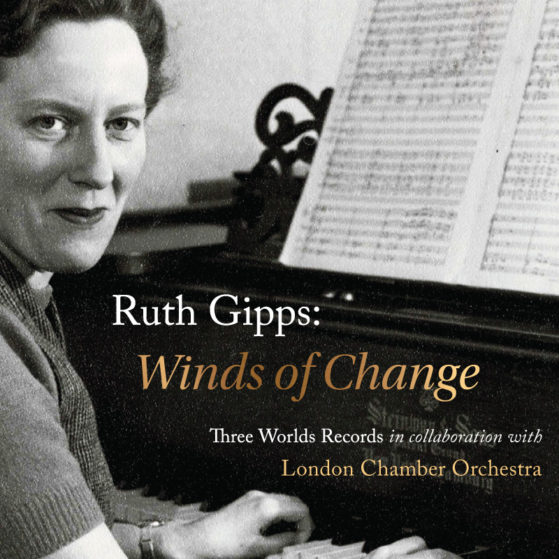

Winds Of Change

Dear listener,

It is with great pleasure that we share this recording of Ruth Gipps’ chamber music featuring the horn. Having first become acquainted with her music via her Horn Concerto op.58 – a work that struck me as a result of its spellbinding virtuosity, orchestral colour and melodic invention – I was shocked to find a fantastic collection of works that had never been commercially recorded and are seldom heard in the concert hall.

The sheer range of instrumentation, style and time elapsed between the first piece of the disc, The Three Billy Goat’s Gruff, Op.27b and the last, her Sonata for Alto Trombone (or Horn) and Piano, Op.80 means that this project offers a real insight into the life and music of the composer. Indeed it is an intensely personal album, not least because her son Lance Baker, a prolific horn player himself, provided the inspiration for much of the horn writing. Her own experience as an oboist is evident in abundance due to the wonderfully idiomatic way that she writes for the winds with each instrument inhabiting its own distinct character, creating the building blocks to the whole of each work.

Ruth Gipps was born on the 20 February 1921. From the age of four when she began astounding audiences with her exceptional musical ability as a child prodigy, she sustained a varied career that lasted over seventy years. To achieve the combination of longevity paired with prominence, especially as a female musician fighting gender prejudice during the twentieth century, is a testament to her remarkable determination and her deep love for music-making. The seed of this resolve and the normality for Gipps for the female of the family to provide was sown with her mother, Hélène. Due to Hélène’s husband’s, Bryan Gipps, professional instability, she set up her own music school which quickly became the family’s reliable source of income. In middle-class English families during this time, such a situation was extremely rare and the Gipps family were somewhat socially outcast as a result. It was, however, this backdrop to her life that provided Ruth Gipps with the necessary character to overcome many obstacles and prejudice that she would face throughout her career. Her attitude towards the regressive compartmentalisation of female musicians can be seen when she expressed her feelings about going to the Royal Academy of Music, “I had protested that I didn’t want to be turned out a neat little College girl in a white frock”.

Gipps’ musical influences include her teacher Ralph Vaughan Williams, Arthur Bliss, Arnold Bax and Frank Bridge. She felt her music to be very typically “English” and very much of the tradition that played on the pastoral, expressive nature of the British countryside. She vehemently rejected the more progressive musical currents developing around her, namely serialism and the avant-garde, and very much remained in the world of tonality and lush orchestration. In the case of a composer such as Sir Malcolm Arnold, a great personal friend to Ruth Gipps, these views did play a role in the relative lack of public performances and support. Ruth Gipps, however, had to face the same lack of support on top of gender prejudice. Within a relatively short space of time, Gipps experienced many “firsts” as a female musician; she was the first female conductor to conduct at the Royal Festival Hall in 1957 as well as the first woman to conduct a work of her own, a BBC broadcast of her Third Symphony in 1969. She was also one of the youngest Doctors of Music in the country, achieving this at the age of 26 and only the second woman to chair the Composers’ Guild of Great Britain after Elizabeth Maconchy.

Throughout her career, Gipps was a pioneer who challenged, head-on, some of the deep-rooted discrimination that had long barred female musicians from the more visible and important positions within music, and indeed wider, life. Perhaps this feeling can best be described by Gipps herself when she said: “I know I am a real composer, perhaps they will only realise it when I am dead!”

It is therefore with great pleasure and gratitude that we can share this album of her works to ensure that her place in British musical history is better appreciated and understood.

– Ben Goldscheider

Memories of Ruth Gipps

My regular encounters with the enthusiastic and encouraging personality of Ruth Gipps were amongst the high points of my student experience.

In the late 1960s, orchestral students were not valued to the extent they are now: during my time as a music student, we were ranked below pianists, organists, string soloists and singers, or so it seemed. Conservatoire principals were not drawn from the orchestral world, unlike today where so many institutions have my colleagues in charge, and so orchestral training was minimal, and disappointing to someone like myself who had experienced intensive sectional rehearsals in various youth orchestras during my schooldays. There were occasional orchestral concerts in colleges, but the characters in charge seemed tired and grey and so many of us looked for experience in amateur orchestras (who then, as now, always seemed to need bassoon players) and chiefly the weekly London Repertoire Orchestra, formed and conducted by Ruth Gipps.

An added bonus of playing in this orchestra was the pleasure of sitting next to Ruth’s husband, the clarinettist Robert Baker, a real professional, who never put a foot wrong and was wonderfully patient with the blundering students surrounding him. Their son, Lance, was a steady presence on first horn behind me.

As for Ruth herself, she tackled the most challenging of pieces with gusto, always with a big smile on her face, and conducted with huge gestures. I never remember her being anything other than positive and encouraging, and she enjoyed her music making immensely.

She was also full of good advice about the orchestral profession, having considerable experience at a time when very few women were to be seen, especially in the wind section. “Always catch the train before the one which gets you there in plenty of time” was one which has stayed with me.

Ruth had many contacts with professional musicians and was able to persuade them to run through concertos with us, a memorable one being her composition “Leviathan” for contra-bassoon and orchestra with the great Valentine Kennedy of the LPO. He also stayed on to play in Dohnanyi’s Variations on a Nursery Theme which contains a challenging solo for the instrument.

There was an annual concert in the Royal Festival Hall (I wonder where she found the funds for this) and I remember playing Also Sprach Zarathustra, The Planets and Brahms’ First Piano Concerto under her baton on different occasions.

It is a real joy to play Ruth’s music again so many years later, and to reignite memories of her – I was asked about her for this recording and my first words were “she was great fun.”

– Meyrick Alexander (bassoon)

1. The Three Billy Goats Gruff Op.27b

Written 1943, the first performance was given as part of the Sheffield Wind Concerts. The date of that performance is unknown.

Written to accompany and bring to life the narration of a Scandinavian folk tale, The Three Billy Goat’s Gruff Op.27b is a work full of vivid imagery, playfulness and is emblematic of Gipps’ affinity for beautiful melodic lines. The instrumentation: oboe, horn and bassoon is such that each represents a different “Billy Goat”, as well as the evil troll! The music opens with the musical depiction of the Three Billy Goat’s Gruff, “Great”, “Middle” and “Little” in their size, grazing in green pastures. The oboe introduces the main theme, a wandering, expressive melody that is supported by an accompaniment in the horn and bassoon. The text follows the Goats as they cross the river, only to be

confronted by Mr Troll, a bully who is eventually knocked into the river by Great Billy Goat Gruff, a moment where the word ‘SPLASH’ and cascading scales in the winds perfectly align.

Narrated by Ruth Rosales

2. Seascape Op.53

Written in 1958 for the Portia Ensemble, the first performance was given in the Arts Council Drawing Room on the 7th October 1960 by the Portia Ensemble, conducted by James Verity.

Scored for ten wind players: two flutes, an oboe, English Horn, two clarinets, two bassoons and two horns, Seascape was written for the Portia Ensemble, an ensemble that Gipps founded herself, made up entirely of women. It is an example of programmatic music, the sounds conjuring up the beauty as well as stormy nature of the sea. It is thought to have been inspired by a trip Gipps took to Kent where she was giving lectures and, during her stay in a coastal hotel, could hear the sea from her bed. The work is in Ternary form with a wonderfully rich rhythmic and percussive central section.

3. A Taradiddle for Two Horns Op.54

The piece was written in 1959 and based on an invented nursery rhyme, “Mistress Mouse”, from “Children” in The Prophet. It was dedicated to her son, Lance Baker and Shirley Hopkins.

Gipps’ son, Lance Baker, was born in 1947 and as such, A Taradiddle Op.54 is a short and sweet work perhaps intended for twelve-year old Lance to both enjoy and be introduced to small-scale chamber music with his horn teacher, Shirley Hopkins. The main theme is a lilting melody, very much within the middle register of the instrument, that is passed between the two horns. The alternation between melody and accompaniment is then expanded to play on the nature of call and response, Gipps perhaps harking back to some of the more functional uses of the horn in its more primitive state.

There are then three variations on the opening theme that follow; a beautifully flowing “Lament”, a vivacious “March” and a “Romance”. The work finishes with a “Finale” that takes us back to the original material of the theme.

4. Sonatina for Horn and Piano Op.56

The Sonatina Op.56 was written in 1960 and dedicated to her son Lance Baker. It received its first broadcast on the 11th October 1967 on the BBC by Alan Civil and David Parkhouse.

Ruth Gipps considered her Sonatina Op.56 as a piece not so much for performance purposes but rather, as a piece designed for students to play so that they can learn about their technique and chamber music playing. The musical quality, however, is very high and the work is extremely playful, expressive and full of changes of character.

The work exhibits some of the several hallmarks of Gipps’ writing for the horn; the long melodic lines and fanfare motifs we hear here were to be exploited to their full potential in her Horn Concerto Op.58, written very shortly afterwards.

5. Triton for Horn and Piano Op.60

Triton was written in 1970 and dedicated to Bernard Robinson.

Unusually, Triton is the only solo horn work that Gipps wrote that was not intended for her son, Lance Baker. Instead, the work is dedicated to Bernard Robinson who was a student at the Trinity College of Music whilst Gipps was teaching there.

According to Greek mythology, the god Triton was the son of Poseidon and the messenger and herald of the sea. The conch shell, one of the earliest ancestors to the modern horn, is one of his primary symbols and he used it to command the waves.

The music is very light in character, the horn opening over the interval of a tri-tone whilst the piano plays in its lowest register, exploring the depths of the sea. There are fanfare motives in the Allegro section which allude to the conch calls of Triton and again, play on the call and response nature that was explored in her earlier work, A Taradiddle for two horns.

6. Wind Octet Op.65

The Wind Octet was written in 1983 for the Janus Ensemble. The first performance was given at the City of London Festival on the 19th July 1985 by the Janus Ensemble.

In 1983, Gipps premiered her Symphony No.5, her final symphonic work and the Wind Octet Op.65 marks her return to writing for chamber ensembles, nearly thirty years after she wrote Seascape. As with a lot of her music, the Wind Octet shows her remarkable ability for motivic development and, of course, melody. Generally speaking, there are one or two instruments with a melodic line, supported by accompaniments in the rest of the ensemble – a textural decision which suggests that a certain level of intimacy should be applied to the ensemble so that the melody can sing through.

7. Wind Sinfonietta Op.73

The Sinfonietta was written in 1989 for the Rondel Ensemble. The first performance was given by the dedicatees, conducted by the composer at Uckfield Music Club on the 17th November 1989. The work received its first London performance at the British Music Information Centre on the 19th February 1991 with the same ensemble and conductor.

The Wind Sinfonietta was to be Gipps’ final large scale, chamber ensemble work. As a result of Gipps’ preference for the larger sound and balance of the double wind quintet (including the tam-tam here), her trio of compositions for wind ensemble: The Sinfonietta, Octet and Seascapes all fall within the tradition of Harmoniemusik, following Serenades for Wind by Dvorak and Strauss.

The work shows Gipps at her best with regards the nuance of her orchestration, tone colour and ability to create landscapes with her compositions. The first horn part is extremely virtuosic and this is a real testament to the growing abilities of her son, Lance Baker. One of the more difficult elements of a wind quintet is balancing the horn with the other instruments but here, with the doubling of the sonorities, that problem is alleviated. The result is a symphonic-like work with the intimacy and nuance of a chamber ensemble.

8. The Pony Cart Op.75

The Pony Cart was written in 1990 for Leonard Paice, Ann Warnes and Stephen Rowe.

The Pony Cart is an example of Parlour music for friends, short in duration, sweet in character and for an unusual combination of instruments. The work is in ABA form, with the flute and horn sharing the melodic lines and the piano providing a characterful accompaniment. The writing for the winds is wonderfully idiomatic, the flute harbouring the more virtuosic material with flourishing scale patterns at the top of its register.

The music is, like so much of her output, very pastoral in its nature and, after a slow and rhapsodic introduction, the horn presents the main theme which has a pompous yet playful character.

9. The Lady of the Lambs Op.79

This work was written in 1992 and commissioned as part of a gift for Elizabeth Yeoman from the Composers’ Guild, to mark her retirement. The first performance was given on the 21st January 1993 at the Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester.

Despite her love for wind instruments, this short work is the only Wind Quintet that Ruth Gipps wrote. Like the Pony Cart Op.73, the music is clearly another example of parlour music. It is one of twenty short songs written as part of an Elizabethan Songbook, written in honour of Elizabeth Yeoman. The text, Alice Meynell’s “The Shepherdess,” describes the English countryside and, quite literally, a Shepherdess-a Lady of the Lambs. The music lilts in a 6/8 time signature, is rhythmically simple and the quintet serves as a humble accompaniment, a colouring, to the text sung by the Soprano.

10. Sonata for Alto Trombone (or Horn) and Piano

Written in 1995, the Sonata for Alto Trombone (or Horn) and Piano is Gipps’ final work and was dedicated to Christopher Hoepelman. The first performance was given on the 14th March 1996 at the British Music Information Centre by Christopher Hoepelman and Sally-Ann Zimmerman.

Despite being written for the trombonist Christopher Hoepelman made sure that the

final work she wrote, her Sonata Op.80, could be played on the horn as well. The work is in three movements, the first being a very majestic, grand affair that seems to be a synthesis of her strongest qualities. The melodic writing is intricate and expressive, the range of the instrument is exploited to great emotional gain and yet, there is still the playfulness of her rhythmic material which we see binding her entire output together like a thread.

The second and third movements could not be more contrasting. The former uses long, expressive, melodic lines and the latter is a virtuoso tour de force. It is an explosion of energy and emotion, a final presto pushing the soloist to their limits as the music closes with rich aplomb.

Ruth Rosales – Bassoon

Hannah von Wiehler – Conductor

Ruth Gipps – Composer

Photos – The Ruth Gipps Archive