Timothy Jackson’s unique and ground-breaking work, Three Worlds. Inspired by M.C. Escher’s eponymous artwork, the nine movements are played simultaneously but can juxtaposed in any order.

When I first got to hear about the Guild of Hornplayers (GoH), the group already had a 14-year history. As the brainchild of Martin Childs, it had been an enthusiastic mix of professional and amateur horn players who performed ambitious programs of horn ensemble music in groupings of all sizes. In those days it was known as the Tony Halstead Horn Ensemble and the name change, which happened early in 2019, came with the blessing of Tony himself, who has retained his position within the group as artistic director, coach, conductor, inspiring musical genius, guiding light and general top bloke.

By the time I had participated in a few GoH events, in Cambridge, Sudbury and Penarth, I was finding myself very impressed by the energy, commitment and philanthropy of Martin Childs in his willingness to experiment, adapt, expand the group’s horizons and try new ideas.

During the summer of 2018 we were discussing the commissioning of new repertoire. Martin was thinking about asking Tim Jackson to write something new and a little light went on somewhere in my head in connection with two string quartets by the French composer, Milhaud, which could be played either separately or simultaneously as an octet. I thought this idea had great potential for two or more horn quartets. Martin called Tim and after a brief rush of emails between the three of us – in which we discovered that Tim had already been thinking of writing such a multi-layered work for horns – Tim got to work writing.

At around that time, I received an invitation for the second year running to visit the city of Tucumán in Argentina. This time I decided not to run an entire international horn course on my own but to lighten my load by bringing some colleagues from GoH with me. We would be a horn quartet, perform some concerts, coach some horn groups and, hopefully, have a lot of fun. Martin set his creative mind to work and soon we had a full program for a nine-day week in Tucumán and Buenos Aires including group coaching and public concerts in four different venues. Tim’s new work was highlighted as the centrepiece of the teaching course and on hearing about this he enthusiastically adapted his writing and added another layer to its already considerable multi-dimensionality; that of working for players at various different levels of attainment. It was to be called, “Three Worlds” after the famous engraving by M. C. Escher depicting a lake with three visible perspectives: the surface of the water with floating leaves, the world above the surface shown as the reflection of a forest, and the world below with swimming fish.

The course we ran in Tucumán had to fit around our rehearsals and the four concerts we presented as the Quartet of the Guild of Hornplayers. Additionally, our coaching and teaching of the horn course participants culminated in them giving two public concerts of horn ensemble music, one of which had Three Worlds as its centrepiece. We had received the newly completed score from Tim some weeks before our trip and had immediately set to work rehearsing it. Superficially, it all appeared relatively straightforward, that is until we took the trouble to read the explanatory text – the small print.

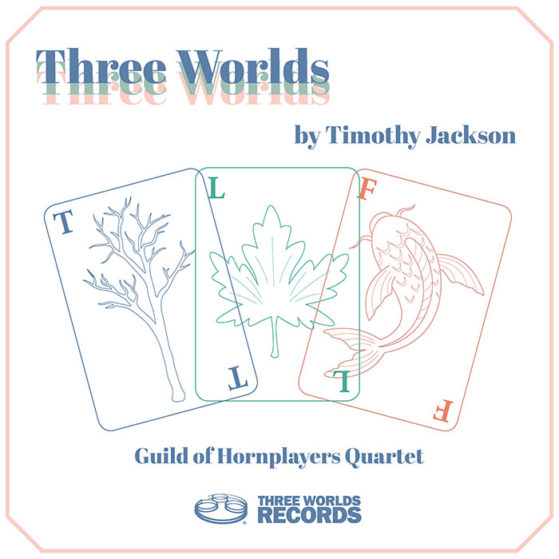

The way the nine movements are sequenced and layered for each performance is deliberately left to chance and is decided, moments before the performance, by drawing lots by means of two sets of cards. A nominee from each of the three groups draws one card from each set.

Sounds complicated? Well, in practice it is not but getting one’s head around it most definitely is.

At the time of our preliminary rehearsals of the work, there were only four of us so we just had to try to imagine what these pieces would sound like when combined into three layers …only we couldn’t. We tried – we failed – but were filled with anticipation and curiosity.

However, we got there in the end. As the engaging centrepiece of a horn teaching course lasting a few days and culminating in a performance for twelve or more participants, Three Worlds fulfilled its brief perfectly.

Some months after returning from Argentina Alex, Hugh, Martin and I met at Henry Wood Hall in London to record Three Worlds. Since we would be layering up our recordings of the nine movements to make a montage-simulation of the whole work we had to be particularly careful about intonation because any errors would only become magnified during the mixing process. During rehearsals we deliberately raised the issue of intonation to new levels of pathological neurosis.

Although the performance in Tucumán had given us a glimpse of the potential of this great new work, we had to wait until we heard the “first edit” mixes before we could really experience the whole thing in all its glory. I’ll never forget the feeling of sheer delight at hearing for the first time how the different blocks of music combine together. The individual movements are without exception beautiful and fascinating jewels, but the way they combine together to make a whole much larger than the sum of its parts – added to the fact that every performance will be tonally, rhythmically and “geographically” quite different – is musically stunning and miraculous.

Our vision at the Guild of Hornplayers is, in partnership with some great composers, to expand the repertoire for the horn in many different configurations and genres. From full symphonic works such as “Speigelstucke” (by Tim Jackson) a companion piece to the Schumann “Concertsucke” through to “Viardilles, a jazz influenced trio for 2 horns and piano (by Jim Rattigan) Over the last 12 years we have commissioned works by great horn players and/or composers alike, including; Richard Bissill, Tommy Hewitt-Jones, Tim Jackson, David Mitcham, Jim Rattigan and Huw Watkins.

All new works are commissioned with a performance in mind, and this was the case for “Three Worlds”, which in time by the way became the inspiration for Three Worlds Records. The Guild of Hornplayers quartet was booked on a tour to Argentina in 2019 where we were also going to be running a coaching course during a week of performances. We wanted to do something a little more imaginative than the standard coaching pieces within which was the difficulty of combining mixed ability students. Thus, the seed was planted.

My good friend, and indeed the first composer we commissioned, Tim Jackson came to the rescue. We talked about a piece that could bring together students of all abilities and could be part of a structured educational course, something that could be performed in concert by all participants. The consistency Three Worlds provides for students and teachers in providing structured coaching sessions is incredible, the results quite different from anything they have ever heard or experienced.

We aim to make our recordings as creative as possible and will always try and bring to the listener new and exciting pieces. Personally, I very much like the companion piece, my thinking is that they encourage performance of new works alongside the more established repertoire they sit alongside. To make these recordings accessible we have set up our own, very niche, label “Three Worlds Records” where you can find incredible new recordings with some great artists.

Pip Eastop contacted me a while ago and booked me to produce and edit his extraordinary and wonderful recording ‘Set the Wild Echoes Flying’, performed brilliantly by Pip on the natural horn with a beautifully delivered spoken contribution by Tony Halstead. The whole process went very well, and Pip was minded to invite me back, together with my old friend and recording engineer Tony Faulkner, to record ‘Three Worlds for Triple Horn Quartet’ by RLPO Principal Horn and composer Tim Jackson.

In Tim’s words ‘This is a piece of music for three quartets of horns. It is nine movements, to be played continuously, without breaks. Starting at the same time but not in the same order. The order of the movements is chosen by drawing lots before the performance begins.’ It should also be noted that Three Worlds reflects music in Minimalist, Atonal and Jazz, so we have three movements in each style.

We booked Henry Wood Hall in London for two days. HWH is one of the best live classical recording acoustics in the UK and having thought long and hard about it, we set up to record basically a horn quartet as we had decided to make this recording using only four players.

Tim’s music is fascinating, playable and most enjoyable to listen to, but as we all wanted the best quality results, we took our time and had plenty of re-takes where necessary. There were opportunities for the players to listen to first runs-through of each movement but fortunately they were comfortable trusting me to spot discrepancies and suggest improvements. I should point out to younger readers that I have the theoretical advantage of having been a professional hornplayer myself (Principal Hallé 1973-86 and Senior Horn Professor at the RNCM 1978-91) so whilst being 100% sympathetic and full of admiration for these superb players I was in a good position to assist in achieving the best results.

Having spent a most enjoyable two days recording I uploaded all the audio files (blessed with Tony Faulkner’s excellent recorded sound) onto my SADiE system and set about producing a 1st edit. This first stage was to get each component quartet movement sounding at its best and from my session notes I was able to work fairly smoothly to create a 1st edit. This was sent through to Pip whose eagle’s ears came up with a number of suggestions for improvements. I duly made as many of these improvements as were possible (almost all) and sent a 2nd edit which again provided Pip with the opportunity to make further suggestions.

With us both having ‘shaken hands’ over the component quartets my next task was to start creating a montage of an agreed sequence of the nine movements, in such a way that it sounded like three groups of hornplayers performing at the same time.

I set the ‘mixer’ within SADiE so that Quartet 1 was to the left, Quartet 2 was in the centre and Quartet 3 was to the right and I gave several options of how far apart the groups would sound before we agreed which was best. In the first ‘montage’ of nine consecutive movements, Quartet 3 begins, followed by Quartet 2 and then Quartet 1. I had to space the entries so that it sounded convincing to Pip and also to Tim, who had joined us at this stage in the process. The second movement began with Quartet 1 followed by Q2 and Q3 and the third movement began with Quartet 2 followed by Q1 and Q3. The remaining six movements were set up in a convincing random sounding order and I tried to make each beginning sound as different as possible and my brief was also to have each movement finish with a long chord.

Eventually we decided that it would most effective to have three consecutive ‘montages’ of nine movements, with the three quartets (left, right and centre) playing together in a seemingly random sequence, each section following a good few seconds of silence. We also decided that we would have the original nine movements played by the central quartet following on from the three ‘montages’ and that is the version that listeners will enjoy. Some nudging and tweaking followed to achieve the best results before Tony Faulkner did some work on the final sound.

I must say that this is a delightful composition, which sounds different every time you hear it. The component nine quartets are gems in their own right and when everything is combined and you can hear the three groups playing from the left, centre and right, the effect is quite mesmerising. I have thoroughly enjoyed working with such fine players on such a tantalising piece of music and I recommend it 100% to one and all.

The initial idea for writing a piece called Three Worlds came to me over 25 years ago, whilst sharing a room on a youth orchestra course with the brilliant trombonist Amos Miller. We discovered a shared love of jazz, mountains, silly jokes and also the artist M. C. Escher.

At the time, I had an enormous poster of Escher’s Three Worlds on my wall and I found it endlessly fascinating. I loved how, no matter how often I looked at the print, it would always take my brain a few seconds to separate out the three ‘worlds’ in the picture. Equally, I enjoyed how my attention would wander through these levels, sometimes drawn to one element, but sometimes able to stand back and enjoy the entire effect.

Amos and I idly batted thoughts around about how this might be represented musically in a chamber piece with tape, with two pre-recorded ‘worlds’ and the third played live. It would be another 25 years, though, before the opportunity arose to put the idea into practice.

Many years later I had a number of conversations with both Martin Childs and Pip Eastop about the Guild of Hornplayers’ first trip to Argentina, and in particular their search for something they might be able to perform with a flexible group of mixed amateur, student and professional hornists. Pip pointed to Darius Milhaud’s 14th and 15th String Quartets, which can also be played simultaneously as an octet, and wondered if something similar might work for two (or even more) horn quartets.

This struck me as a brilliant idea, meaning that the individual groups would be able to rehearse separately but then perform together with a minimum of rehearsal time as a full ensemble. I also realised that this might be just the opportunity I had been waiting for with Three Worlds, and now it might even work without having to pre-record anything, with all three groups playing live.

The actual number of players who could be involved was unclear, so I had to write with the possibility that each part might be doubled – and with a large potential number of performers, the practical challenge of being able to synchronise everything was right at the front of my mind.

In the end, it was Escher’s lithograph itself that provided the solution. The leaves on the surface of the water are not synchronised with the fishes, any more than they are synchronised with the trees! They occupy the same the space at the same time, but they are independent. Thus, I would write for each horn quartet to be self-contained, but with the precise timings between the groups left flexible. As long as the different metronome speeds were followed reasonably closely, each quartet would ‘swim’ between harmonic worlds at broadly the same time.

So: we have nine movements, divided into three ‘worlds’ of Minimalist, Jazz (or, at least, swing) and Atonal music. Each of these three worlds has three further divisions: ’Trees’ music, which is heavy and deep-rooted, ‘Leaves’ music, which is flowing and floating, and ‘Fishes’ music, which is darting and energetic, and always played either muted or hand-stopped.

Each quartet plays all of the nine movements, but not in the same order. In a live concert, the order is determined by drawing lots before the performance begins. The shape of the piece, therefore, is intended to be as unpredictable as the scene Escher depicts.