Set The Wild Echoes Flying began as a short piece lasting just a few minutes which I wrote in response to being asked to perform “some kind of encore” at the end of an orchestral concert with my beloved London Chamber Orchestra. I couldn’t think of any existing work suitable for performing immediately after Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony (!) so I decided to compose something myself with the intention of it being perhaps amusing rather than having any musical value. I chose to use the “natural horn” more for fun than for any other reason.

At around the same time I was asked by Alison Balsom to perform something at her “Brass For Africa” charity concert, so I wrote another single piece, again for natural horn. By way of an introduction to its performance and to make it seem as relevant as possible I described it as being full of African animal sounds; elephants, monkeys, birds etc. The human imagination is so marvellous and adaptable that some members of the audience I spoke to afterwards reported hearing all the right kinds of creatures.

During the weeks following these performances, encouraged by positive reactions from both audiences, I continued working on the two pieces and both grew in length and complexity. Then something strange and unexpected happened; each one split into two separate movements and each of these continued developing and expanding. This was new to me, as I had never before considered myself to be a composer.

I’m not sure if it was a conscious thing but all four movements seemed to contain traces of Britten’s Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings. Having noticed this while the movements were still growing I encouraged it to happen more and from there came the idea of using some of the same poems chosen by Britten as spoken interludes between the four movements. Next I decided to borrow various lines from those poems to use as titles for each movement and for that of the whole piece.

I enjoyed writing all these movements specifically for the natural horn and at every point in the process it seemed to feel just right. By way of justification, if any is needed, I like to think that the natural horn deserves to be considered, even in our modern times, as a perfectly good and valid instrument in its own right and not merely as a historical artefact. Despite the simplicity of the natural horn and its apparent lack of a full chromatic stock of notes it is a surprisingly capable, if idiosyncratic, instrument. Most things seem to be playable on it – albeit sometimes as the result of desperate struggles – and it came as a surprise to me that at no point during the writing of any of the four movements did I find the instrument unable to do something I wanted to add.

By the time the classical period was coming to a close the natural horn had reached a state of perfection in its design and build. Sadly, at this point it was displaced, to the point of near extinction, by the arrival of the new “modern” horn with its valves and enhanced capabilities. The brilliant concept of having seven (and, later, twelve with the “double” horn) differently pitched (or lengthed) natural horns conveniently combined together into one mega-instrument was so exciting for composers that they ceased writing for the natural horn altogether and the whole world completely forgot about it. For a couple of hundred years the natural horn effectively disappeared from our musical culture and could be found only in encyclopedias, museums and dusty attics. The wipeout was so thorough that even music which had been composed specifically for the classical, natural horn came to be played exclusively on valved instruments! I imagine that future generations will look back on this particular fact with curiosity, whereas my generation and several before ours never gave it a thought as we performed musical treasures by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven using instruments which those composers would never have imagined.

From the seventies onwards the early music movement began putting the natural horn back on our musical map. This rekindling of knowledge and interest in earlier instruments has had the result that natural horns are now back in production in many workshops around the world and are commonly used in orchestras and ensembles for performing music from the classical period. Horn makers of today are still making slight adjustments to their conical tapers searching for tiny improvements of intonation and resonance, but the thing was, and is, essentially perfect and has been so for hundreds of years. I believe that now is the right time to be bringing the natural horn out of musical museums and giving it some new music of its own.

***

The first movement is called A Monstrous Elephant (the words clipped from Charles Cotton’s poem, “The Evening Quatrains”, which was used by Britten in his “Pastoral”), a name which nicely links it to the original version I played at the “Brass For Africa” concert. I found that by rhythmically repeating glissandi and using a variety of careful hand-stopping techniques I could create an illusion of chordal harmonies. There are also some quite strong hints at Britten’s “Prologue” here and a couple of little cadenzas featuring whole tone scales. I suppose I’m keen to show how much harmonic freedom there is available despite the limitations of having only one single harmonic series to play with.

I know I am not the only horn player who believes that the finest movement in our Serenade by Benjamin Britten is the one which doesn’t feature the horn at all. During that movement, entitled “Sonnet”, the horn soloist is heading backstage to get ready for the final “Epilogue”. Thus, I wrote Turn The Key Deftly with the deliberate intention of reclaiming “Sonnet” for horn players. The melodic line wasn’t too difficult to bend to fit the natural horn and I have tried my hardest to hint at some of the powerful harmonic contortions invented by Britten for his string orchestra accompaniment by using a sung part to give a chordal accompaniment to the horn line.

Blow Bugle Blow started as a playful and somewhat childish “jazzing up” of the melody from the Serenade’s “Hymn” – Britten’s answer to the rondo movements in Mozart’s horn concertos. But then I got myself rather caught up in it and slowly it transformed into a highly chromatic and rather serious blues.

The encore piece I began with eventually became the final movement of Set The Wild Echoes Flying and I called it The Horns of Elfland. This movement has the added dimension of a backdrop of sound, a drone, which can be provided by any combination of instruments capable of sustaining a concert C very quietly for a few minutes. So far I have performed it with a string orchestra, string quartet, four tubas, four horns, 12 horns and 30 horns. I’m not sure which I like best as they all seemed to work equally well.

Photographs by Pip Eastop

Acknowledgements

My thanks to:

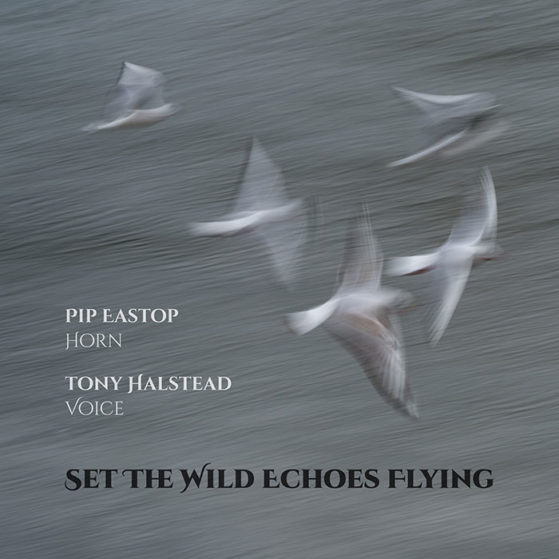

Amos Miller for his stunning image Gulls over the Thames. (© Amos Miller 2019)

Alison Balsom and the London Chamber Orchestra for getting me started.

Martin Childs for retrospectively “commissioning” the work and organising its transcription, various performances and this recording.

Anthony Halstead, to whom the work is dedicated, for being a friend, a colleague, an inspiration, a guide, a teacher …and for being the world’s greatest player of the natural horn.

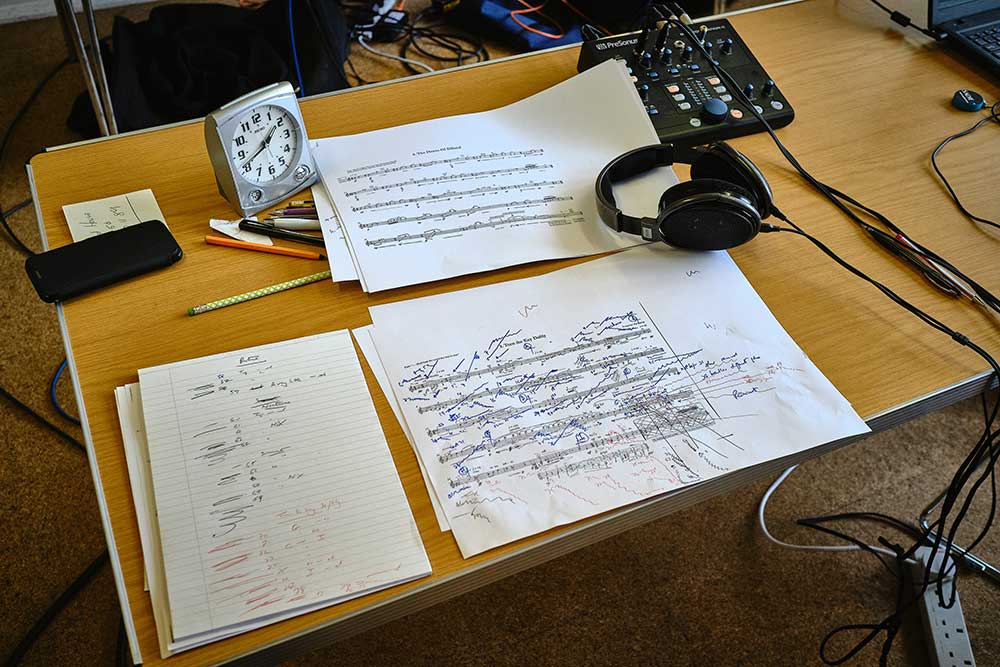

Guy Llewellyn and Ann Barnard for their extreme levels of patience and expertise in turning my scribbles into printable pages.

The lovely audience of mostly octogenarians for their enthusiasm at the first complete live performance of the work in Sudbury, Suffolk, in May 2016.