About the Back To Back To Back

This album follows on from two previous ones which are called “Hornwaves: Quartets for Solo Horn” (myself), and “Back to Back: two part discoveries for horns” (myself and Jonathan). All three were freely improvised and all were recorded in the highly stimulating acoustic of St. Silas The Martyr, Chalk Farm, by the equally stimulating engineer, Mike Skeet. Without him, none of this peculiar music would have come into existence; so many thanks to Mike. My thanks also to Jonathan and Richard for lending their unique talents in such a harmonious and democratic way.

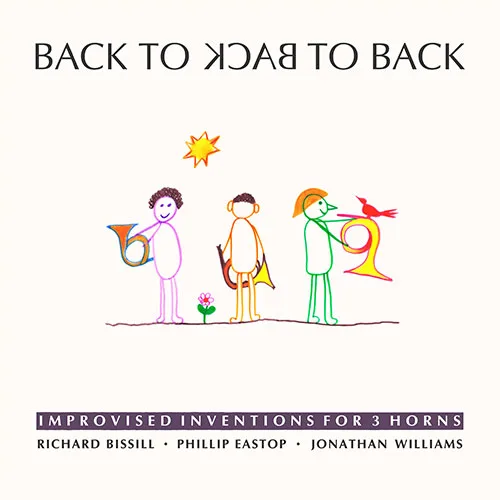

For the third album, the addition of Richard Bissil to make a trio was an obvious choice despite our never having improvised together before. His playing is well known for its combination of mercurial musical wit, Chevrolet-like smoothness and power, and extraordinarily agile grace. He, like Jonathan, is an inspiration. (The technically minded might like to know that throughout the recording Richard played a Yamaha double horn, Jonathan played an Alexander single B♭+A horn and I played an Alexander 103 double horn).

Our approach, as for both of the previous albums, was simply to start the tape machine rolling and make up lots of pieces over a couple of days, sifting through them afterwards to find the best ones for the album. As it happens we have kept about a third of what we recorded and the pieces are presented here in the order in which they happened. The titles were added later just for fun. “Overtures” was the very first piece we played and “God Help The Queen” was the last. We agreed to stop at that point because things were clearly getting silly.

Before each attempt at a piece we would sit in our chairs, carefully positioned for the best stereophonic sound (difficult with three horns in a rectangular hall) and discuss how we might begin, which one of us would take the lead and who might be first to follow. We would also usually agree beforehand on some kind of tempo, mood or style. Sometimes we decided to start recording with no ideas at all to see what would happen, but at the opposite extreme, as in “Fanfare” we spent a few minutes scribbling a dozen or so notes down. Definitely cheating! (Incidentally, this piece has a more spaced out sound than the others because we re-positioned ourselves to the sides and end of the hall).

In order to give a unified form and style to what might otherwise have been three disconnected lines of solo improvisation it was important that we listen very carefully to each other whilst playing, to catch any material which could be echoed, developed, exaggerated, extended, decorated, accompanied or used as accompaniment, or simply left alone. The result is music which seems to have a peculiar coherence of its own.

One inherent characteristic of the French horn which can cause problems is the way that its sound projects out behind and to the right of the player. We discovered that when we sat in such a way as to have eye contact our bell flares would point away from each other. This made analytical listening difficult for us, because our sounds spread out through the church before returning, richly dressed in the complex reverberation of St. Silas’. On the second day we tried sitting “back-to-back-to-back” and found that it gave us a much clearer and more immediate aural impression of what we were all up to together. From then on we were playing without eye contact, getting clues and cues only from what we could hear, but this lack of contact made us heavily reliant on luck for our beginnings and endings, adding an extra tantalising frisson of insecurity and suspense. Most of the pieces presented here happened on the second day of recording.

St Silas has, without doubt, a wonderful resonance with the sound of French horns, which is why we chose it, despite its noisy location. You may hear the shouts of children playing outside and the throb of aeroplanes overhead. In “Slow Ripples” Richard and I were well into the piece when a synchronistically influenced jet plane strayed into Chalk Farm air space. We carried on playing, despite the interference, because we enjoyed the way its engines joined in with us on some of the notes we were just about to play … Serendipity!

Pip Eastop 1994

Introduction to Back To Back To Back:

Pip Eastop writes:

It happened late in 2016 that the three of us were quite by chance in the same place at the same time on a commercial recording session. How huge is the music scene in London that it had taken twenty four years for this to happen? Inevitably we found ourselves talking about “Back To Back To Back” and what it had meant for us. We agreed that we should find the old CD (in fact, I found a big box full of them) and put it where it could be heard by more people. So that’s what this is – a refreshed, remastered relaunch of our 1994 album of music which we had created simply by playing together, carefully avoiding the use of composers, conductors and rehearsals.

Remastering:

Huge thanks to Bernard O’Neill at Grand Duc Studios, Midi Pyrenees, for his masterful 2018 remastering of Back To Back To Back.

Bernard O’Neill writes:

Firstly let me say that Mike Skeet was a genius and a wonderful engineer. The sound of this album is totally natural being as it was recorded in the round (or in the triangle) in an enormously noisy and vibrant church. The levels that Mike recorded at were purposefully high and bordering on hysterical but he did this because he knew his home-made pre-amps really well and had checked phase issues out well in advance. Twenty-four years later I made some slight adjustments and with the benefits of some great plug-ins was able to just shave off some of the brashness from the recording without the loss of spirit and flare that the performers put into it in the first place. A well appointed multiband compressor allowed some of the previously unheard midrange to sing through and tamed some of the more strident tones in the climax of “Desk Ants”.

R.I.P Mike Skeet:

Mike was a brilliant eccentric, a very talented and highly respected recording engineer and a man with an unquenchable and infectious passion for all things audio which he was always happy to share with like-minded people. He was perfect for our recording needs, being enthusiastic and willing to experiment. Always favouring ‘minimal’ microphone techniques, Mike’s preference was the classic stereo pair, occasionally supplemented with a few ‘spot’ mics when the layout or acoustic made it necessary. Mike was very well-known for his intriguing DIY dummy-head arrays constructed from balsa wood, kitchen sieves, and foam – but they typically contained superb Schoeps microphones and produced glorious recordings. His home-made equipment looked a bit “Heath Robinson” and this was a recognisable part of his eccentric nature. His electronics were typically built into unpainted tin boxes plastered with Dymo labels, adhesive tape and coloured stickers.

We tried to get in touch with him to ask if he would contribute a few words to this re-release, only to discover that he died in December of 2015.

Musings and reminiscences about Back To Back To Back:

My first instrument was the recorder, which I learned in a group at school and at home with my Dad, who was a great teacher. Dad already played the oboe but he started learning recorder at the same time as me, with the intention of helping me along. He didn’t practise much, whereas I did, sometimes even while walking to and from school. I soon became rather better at it than Dad and I think this early success made me feel terribly pleased with myself and made me work on it even harder. I would play everything I could think of by ear, in every key I could manage. A couple of years later, I started learning to play the horn. I was soon playing everything I could think of – all the tunes I had learned on the recorder – again in all the keys. I say “think of”, but there wasn’t really much thinking involved. I did it all by ear, without necessarily being conscious of what notes I was playing, watching my fingers fumble around to find the right notes. In other words, I learned by ear and from improvisation. Reading music was an add-on, something I learned along the way but which always seemed to me nothing more than a way to reproduce music written by other people, one step removed from the more real, immediate, creative activity of playing whatever arises in the mind’s ear. I was very pleased to meet and befriend two other horn players who seemed to be “wired up” in a similar way – and of course these were Richard Bissill and Jonathan Williams.

At 19 I was very lucky to get a wonderful job in the London Sinfonietta. In those days it was marketed as the world’s finest (or perhaps the world’s only) contemporary music ensemble. It was exciting and quite often as scary as hell. We performed and recorded the very latest compositions, many of them written by deluded accountants who thought they were musical geniuses sent to planet Earth to show humanity revolutionary new ways of making music. Often their works were without melody, without recognisable rhythm, without what might be called harmony, and mostly paid no regard to any kind of musical tradition, trying above all to sound completely new and original. Music critics and reviewers always wrote enthusiastically about our concerts and all the lovely new clothes worn by the latest emperors of composition. But, amusingly to me, rather than sounding original, this stuff all came out sounding exactly the same; a horrible mess. As with paint, if you mix all the colours together you always end up with brown. I always felt sure that we could just make up better music on the spot and it always bothered me that such precisely yet badly notated and unmusical music could receive so much attention and praise.

Born out of this frustration I made an album of improvised music. I booked the wonderful Mike Skeet as sound engineer and producer and we used the church of Saint Silas the Martyr in Kentish Town, London. The music was a collection of horn quartets, created by layering recordings of myself. I called it “Hornwaves” and it was released in the early eighties on audio cassette.

Some ten years later, in the same location and again with Mike Skeet, Jonathan and I made a completely improvised recording which we called, “Back To Back – Two Part Inventions for Horns”. The rearward-facing nature of our instrument brought with it some unexpected problems, one of which was that playing face to face in a large acoustic space meant that we couldn’t hear each other very clearly. So we turned ourselves back to back. A couple of years later, for Back To Back To Back, now with the addition of Richard Bissill, we adopted this same principal, discovering that with our bells facing the central point of an equilateral triangle, we could hear what was going on with perfect clarity. Of course, the three of us were now looking outwards, each unable to see anything of the other two, which presented some signalling problems. I like to think, however, that this visual handicap actually fostered an enhanced focus on listening our way through the creative process.

It’s interesting to try to describe the process of improvisation, it being somewhat a novelty for instrumentalists like us who usually play by reading from musical notation. For me it starts with hearing something in my imagination. Whether I dream it up myself or it comes into my head through the holes on either side – it doesn’t matter – it is the stimulus to make some kind of music to go with it. It may be a tone, or a melody or a rhythm or some kind of accompanying figure. Actually, I have that urge whenever I hear something, anything – the urge to play along with it, below it, above it, alongside it. I always noticed that Jonathan and Richard were just the same in this respect.

Listening now to Bernard’s remastered version feels as poignant to me as looking at old sepia-toned photographs. I find myself transported back in time. Strangely (and I feel a little odd admitting to this) what I hear is all myself. I wonder if J.W. and R.B. experience the same strange illusion – that they are each playing all of it.

My hope is that this album will broaden the way people think about the horn, its nature and its potential.

I’ve always been interested in the nuts and bolts of musical language; intervals, how harmony works, where it leads etc. I’ve always wanted to improve my playing by ear and do remember in the past analysing melodies in my head as I walked along in my own little world – what’s that interval? what’s that chord? what’s the inversion? what note is in the bass? etc. My parents were not musicians but my mum used to sing her favourite songs to me and I would play them right back at her, inventing harmonies that I felt would fit.

I grew up in Loughborough and was a member of the Leicestershire Schools Symphony Orchestra throughout my teens. This was my world and looking forward to rehearsals every Saturday morning got me through the school week. I also played in the BBC Radio Leicester Big Band, led by Roger and Christine Eames. They were very kind to me and encouraged me to improvise solos with the band and to write my own pieces for the band to perform. I had the urge to write music from quite an early age and once I took up the piano I began to engross myself in the wonderful world of harmony that a piano can deliver instantly.

My teacher at the Academy was James W. Brown, OBE, Hon. RAM. (1928-1992). I had come down to London for monthly lessons from about the age of 15 and then continued with him until I left the RAM aged 21. After a few years I moved to the LPO to play alongside the late, great Nick Busch. Sharing the principal horn job with him was a joy and inspirational. What a player he was! Fearless, sensitive, powerful and a huge character. Those early years were very exciting for me as a 22 year old. There were still plenty of so-called “characters” around; before orchestras got all politically correct and demanded more anodyne behaviour from their members. There were some outrageous goings-on which just would not be tolerated now.

I seem to remember just blithely going along with Pip’s curious project. We turned up at St. Silas with no preparation or a plan and just sat down and began. Before each track we would decide who would start it and in what sort of style and that was it – off we went. There were a few false starts or moments where we all quickly agreed that the track was going nowhere. There were some in which we broke down, laughing. But mostly we were fired up and feeling inspired by what we heard ourselves doing in that lovely acoustic.

Most of the track titles were dreamed up by Pip, although “Al Pawns His Alp Horns” was mine. They seem to sum up the music rather well, almost as if we’d named the tracks in advance. In many cases it sounds to me like there are more than three players. In fact only in one track, “Moonlit Caverns of Ice”, did we overdub ourselves, adding three more parts as an experiment.

I remember the sheer fun of recording “God Help The Queen”. Simply letting rip with no regard to what comes out is cathartic,liberating and hilarious and is the opposite of what is normally required of orchestral horn players. I’ve often had the urge in a really quiet, delicate moment in a high pressure orchestral concert to stand up and blast out something wildly inappropriate. It would be a good way to get fired …so maybe I’ll save that for my last day before I retire.

At its best, improvisation can be very liberating, creative and satisfying, almost to the point of feeling like an out of body experience. It’s a sort of unexplained musical magic compared to the predictability of playing previously composed music. Those three days in ‘94 all seem so long ago now. I listen to the results of our recording sessions now and can’t quite believe we did it. I think it sounds incredible.

When I was growing up at home we had a piano and although it was behind a firmly closed door to prevent much of its sound escaping to rest of the house, we could all still hear what was being played. For years all my brothers and sisters played it in their own individual ways. Sometimes we all played together with our mixture of instruments: tuba, horn, trumpet, violin, oboe, recorders and voices. Nobody made us play – we just did it because we liked it. We were brought up singing along with our parents to recordings of massive Welsh choirs with thousands of voices, so I learned how to harmonise before I could actually read music.

For Pip’s new recording project, Back To Back To Back, It was impossible to know how to prepare. Pip and I had played together for years but I hadn’t yet worked with Richard. I had no idea what it was we would be aiming for so I opted for practising in as many different musical styles as I could – from Bach to Charlie Parker – as the best approach for getting into shape for tackling the unknown. When it came to the actual recording I tried to focus entirely on listening as intently as possible and maintaining a three-way conversation between our very different instruments and playing styles:

I remember that in some of the pieces we ran out of creative steam, so we just stopped, with no sense of loss or failure, and began something else instead. On the second day I think we felt a little more free and confident and were able to let ourselves go a little more. When we reached our final track, “God Help the Queen”, it felt as though if we went any further in that direction we would be risking physical rupture.

Some experiences are so big that you never feel the same the same again afterwards. Back To Back To Back was such a milestone for me and I remember those two days as an entirely unique experience. Improvisation for classically trained musicians can be intimidating because it involves a huge change in attitude, and preconceptions.

Somebody once said that you can only really judge a recording you have made after a long time has passed. I am still waiting for some of my recordings from long ago to appeal to me, but Back To Back To Back makes me laugh every time I hear it and I think it will accompany me into my old age as one of the most interesting things I have done. I feel extremely lucky to have been so creatively involved and to have ventured so far outside traditional horn playing. Provoked by Pip’s unique enthusiasm, I believe we struck a creative vein.